When a traumatic event strikes, Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) provides a structured approach to help individuals process their experiences and reduce the risk of long-term psychological harm. Developed by Dr. Jeffrey T. Mitchell in 1974, CISD is a seven-phase group intervention designed primarily for first responders but now widely used across sectors like healthcare, aviation, and business.

Key Takeaways:

- Purpose: CISD helps participants process trauma, normalize stress reactions, and identify those needing further professional support.

- Timing: Sessions work best when held within 24–72 hours of the incident.

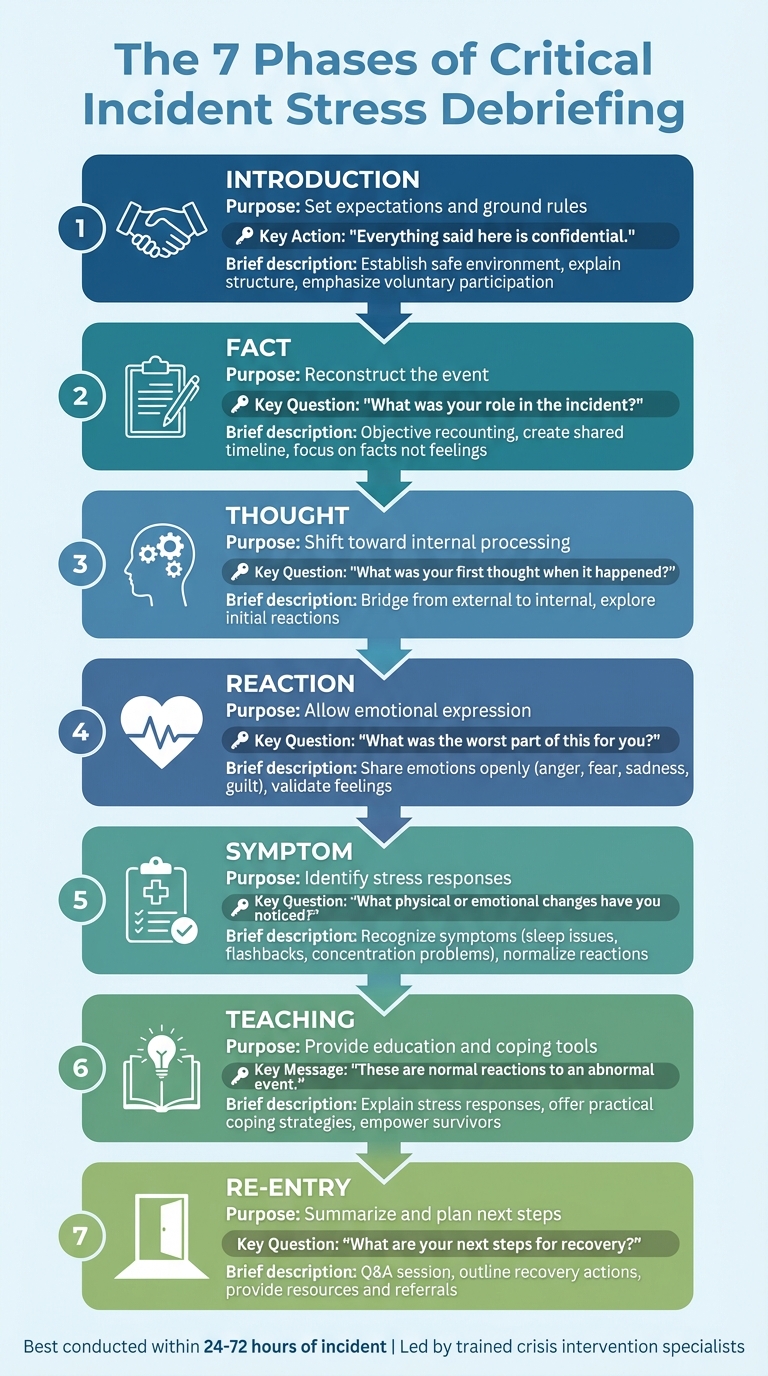

- Structure: The seven phases (Introduction, Fact, Thought, Reaction, Symptom, Teaching, Re-entry) guide participants from recounting the event to emotional recovery and practical next steps.

- Principles: Voluntary participation, confidentiality, and a structured approach are central to its success.

- Facilitators: Trained professionals lead sessions, ensuring a safe space and offering coping strategies.

CISD is not a replacement for therapy but serves as “psychological first aid”, providing immediate support while paving the way for long-term recovery. Early intervention can prevent stress from escalating into conditions like PTSD.

How Do You Conduct Critical Incident Stress Debriefing?

sbb-itb-17645e5

Preparing for a Critical Incident Debriefing

Getting ready for a critical incident debriefing is all about setting the stage for healing, not adding to the stress. By focusing on the core principles of CISD (Critical Incident Stress Debriefing), you can ensure the session helps participants process trauma effectively. Everything you do beforehand – like evaluating the need for a session and choosing the right facilitator – directly influences how well the debriefing works.

Determining When a Debriefing is Needed

Not every tough situation at work calls for a formal debriefing. The key is to figure out if the event has disrupted normal functioning. Events like sudden deaths, serious injuries, or workplace crises often require debriefing, especially if they’ve had a noticeable impact on employees’ mental or physical well-being.

The clearest sign to proceed is when people show strong reactions – both emotional (like shock, anger, or fear) and physical (like trembling, sweating, or sleep issues). Certain workplace incidents, such as a co-worker’s death or suicide, near-miss accidents, or events that attract heavy media attention, should always trigger a debriefing. Behavioral changes like withdrawal, absenteeism, or a drop in productivity are also red flags.

Timing is everything. Aim to hold the session within 24–72 hours to get the best results.

Creating a Safe Environment

The space where the debriefing happens plays a big role in whether people feel comfortable enough to share. Confidentiality is non-negotiable – what’s said in the room stays private, except in cases involving threats of harm or abuse.

Choose a quiet, private location and assign someone to ensure there are no interruptions. Phones, radios, and other devices should be silenced. Group dynamics are also important. Participants should have similar roles and levels of exposure to the incident to create a sense of shared understanding. Keep the group size manageable – 25 people is the upper limit for effective discussions.

“CISD relies heavily on participants sharing their descriptions, thoughts, and feelings in a safe, non-threatening environment”, explains Tanya J. Peterson, NCC, DAIS.

If someone steps out during the session, a facilitator should check on them to provide immediate support. After the session, offering refreshments can help participants ease back into their routines. Teams should stay out of service for about an hour afterward to decompress further.

Choosing a Trained Facilitator

The facilitator is the backbone of the debriefing process. They should be a trained crisis intervention specialist who knows the CISD framework inside and out. Their role is to guide participants through all seven phases of the process while identifying anyone who might need additional professional help.

Using an external facilitator is often the best choice to ensure objectivity and avoid workplace politics. A skilled facilitator will normalize participants’ reactions, helping them understand that their feelings are typical responses to an unusual event.

Key responsibilities for the facilitator include upholding ground rules, maintaining confidentiality, keeping conversations on track, and teaching stress management techniques participants can use right away.

“The aim is to reassure the person undergoing the program that what they’re experiencing is normal, natural, and valid”, notes FatFinger.io.

Facilitators should also have a list of professional resources for referrals. They need to recognize signs of ongoing issues like anxiety, depression, or substance use and connect individuals with appropriate support.

With solid preparation and the right facilitator in place, the debriefing can move smoothly through the seven phases of the CISD process.

The 7 Phases of Critical Incident Stress Debriefing

7 Phases of Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) Process

After setting the stage, the debriefing process unfolds in seven structured phases. These steps are designed to guide participants from recounting the incident to addressing their emotional responses and planning for recovery. Each phase builds on the previous one, moving from external facts to internal experiences and back to practical solutions. Here’s a breakdown of the process:

| Phase | Purpose | Key Question/Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Introduction | Set expectations and ground rules | “Everything said here is confidential.” |

| 2. Fact | Reconstruct the event | “What was your role in the incident?” |

| 3. Thought | Shift toward internal processing | “What was your first thought when it happened?” |

| 4. Reaction | Allow emotional expression | “What was the worst part of this for you?” |

| 5. Symptom | Identify stress responses | “What physical or emotional changes have you noticed?” |

| 6. Teaching | Provide education and coping tools | “These are normal reactions to an abnormal event.” |

| 7. Re-entry | Summarize and plan next steps | “What are your next steps for recovery?” |

Phase 1: Introduction

Facilitators start by introducing themselves and explaining the purpose and structure of the session. They establish ground rules to ensure a safe environment, emphasizing confidentiality, voluntary participation, and the absence of judgment. Participants are assured that no recording devices will be used. The goal is to create a space where everyone feels comfortable sharing their experiences.

Phase 2: Fact Phase

In this phase, participants focus on recounting the event objectively. They describe their roles, observations, and actions, aiming to piece together a shared timeline of what occurred. Emotions are set aside for now, with facilitators gently steering the discussion back to facts if feelings begin to surface. This factual recounting lays the groundwork for the emotional exploration that follows.

Phase 3: Thought Phase

Here, the focus shifts to participants’ initial reactions during the incident. Facilitators ask questions like, “What was your very first thought when you realized what was happening?”. This phase acts as a bridge, helping participants transition from external details to their internal responses, preparing them for deeper emotional processing.

Phase 4: Reaction Phase

This is where participants openly share their emotional responses – whether it’s anger, fear, sadness, or guilt.

“Debriefing allows those involved with the incident to process the event and reflect on its impact”, says Joseph A. Davis, Ph.D.

Facilitators validate these emotions, emphasizing that such feelings are natural responses to extraordinary events. This acknowledgment helps reduce isolation and fosters a sense of shared experience among participants.

Phase 5: Symptom Phase

Participants identify any physical, emotional, or cognitive symptoms they’ve experienced since the incident, such as trouble sleeping, flashbacks, or difficulty concentrating. Facilitators normalize these reactions, explaining they are common after critical incidents. They also watch for signs of more severe issues, like substance misuse or extreme withdrawal, which might signal the need for professional intervention. Sessions typically involve two facilitators: a licensed mental health professional and a peer with a similar background to the participants.

Phase 6: Teaching Phase

Facilitators take on an educational role, explaining typical stress responses and offering practical strategies for coping. They reassure participants that their reactions are expected under such circumstances.

“The main goal is to both inform and empower survivors in order to help them build resiliency (the ability to ‘bounce back’) and return to normal, healthy life”, notes Study.com

This phase equips participants with tools to manage their stress and regain a sense of control.

Phase 7: Re-entry Phase

The debriefing concludes with a summary of the session and a Q&A period. Facilitators help participants outline actionable next steps for recovery and provide additional resources or referrals for ongoing support. After the session, informal conversations over refreshments may encourage further connection before participants return to their routines. Facilitators also follow up in the days after to check on participants’ well-being and assess whether anyone might need further help. Historical examples, such as the support offered after the Oklahoma City bombing, highlight how structured CISD can aid long-term recovery. This final phase ties the session together, guiding participants toward continued healing and resilience.

Common Challenges and Best Practices in CISD

When it comes to Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD), even the best-laid plans can face roadblocks. Participants might hesitate to open up due to fear of being judged, the emotional toll of revisiting trauma, or concerns about confidentiality. On top of that, different incidents often demand tailored approaches to address their unique dynamics. Tackling these challenges head-on is key to making the debriefing process both supportive and effective. Below, we’ll explore strategies for overcoming resistance, safeguarding confidentiality, and customizing debriefings to fit specific scenarios.

Handling Resistance to Participation

Even in a well-prepared, safe environment, resistance from participants can arise. To address this, facilitators should emphasize from the start that participation is entirely voluntary and not tied to any form of evaluation. If someone chooses to step away, it’s important for a team member to check in with them individually, providing immediate support and gently encouraging them to rejoin. Additionally, involving peer supporters – such as colleagues with similar experiences, like fellow paramedics or firefighters – can help build trust and ease participants into the process.

Protecting Confidentiality and Building Trust

Confidentiality is the backbone of trust in any debriefing session. At the start, facilitators must clearly outline confidentiality rules, assuring participants that what’s shared will stay within the group – except in cases where safety is at risk, such as threats of violence, suicidal thoughts, or mandatory reporting situations like child or elder abuse. Simple measures like posting a “CISD in progress” sign, limiting room access, and silencing devices can further protect the session’s privacy and foster a sense of security.

Tailoring CISD to Different Scenarios

While CISD follows a structured format, it’s flexible enough to adapt to the nature of the incident at hand. Not all critical incidents are the same, so the approach should reflect the specific circumstances. For example:

- Workplace accidents might benefit from structured, factual recaps to clarify events.

- Incidents involving children may require immediate debriefings to address heightened emotional distress.

- Natural disasters might call for a stronger focus on restoring a sense of safety.

- Line-of-duty deaths demand specialized oversight to address the profound emotional impact.

A real-world example of this adaptability comes from the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. Systematic debriefing efforts during that tragedy played a significant role in preventing long-term psychological harm.

Conclusion

Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) isn’t just a one-time meeting – it’s a structured approach designed to provide psychological first aid after traumatic events. By following its seven-phase process, organizations can help participants process their emotions, normalize their reactions, and potentially lower the risk of developing chronic PTSD, depression, or substance use disorders. For example, research on police officers showed that those who received CISD within 24 hours experienced fewer symptoms of anger, stress, and depression during follow-up assessments.

But CISD’s impact goes beyond individual recovery. It fosters a sense of connection within teams by uniting people who’ve shared the same traumatic experience. This reduces feelings of isolation and can even improve overall team performance. A review of 15 studies highlighted how non-mandatory CISD sessions helped healthcare workers in emergency settings build stronger coping skills and reduced trauma symptoms.

That said, while CISD offers immediate relief, long-term recovery demands ongoing support. It’s important to view CISD as a starting point, not a substitute for professional therapy. Organizations should implement follow-up steps like phone check-ins, on-site visits, and clear referrals to mental health specialists. Trauma recovery is a journey – some symptoms appear right away, while others may emerge weeks or months later. Ensuring a smooth transition from debriefing to continued care is key to reinforcing the recovery process.

For additional resources on recovery and addressing substance use challenges, visit Sober Living Centers.

FAQs

Who should attend a CISD session?

Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) sessions are designed for anyone directly involved in or affected by a traumatic event. This includes emergency responders, trauma survivors, and community members who have experienced the incident firsthand. These sessions provide a structured environment to help participants work through their emotions, strengthen their coping abilities, and begin the recovery process after facing such intense situations.

What if someone gets overwhelmed during the debriefing?

If someone becomes overwhelmed during a critical incident debriefing, it’s crucial to prioritize their well-being. Facilitators can pause the session, offer reassurance, and allow breaks to help ease the situation. If necessary, they can also provide referrals for professional support. Acknowledging their emotions and encouraging self-care or follow-up assistance can play a big role in their emotional recovery. Having clear steps in place for managing distress ensures the debriefing process remains supportive and effective.

How do you know when to refer someone for professional help?

If someone experiences emotional or physical symptoms – such as severe anxiety, depression, confusion, nightmares, or dizziness – that last for more than a few days or weeks, it might be time to suggest professional help. Signs like trouble focusing, overwhelming feelings of helplessness, or disruptions to daily life are strong indicators that intervention could be beneficial. Additionally, ongoing guilt, deep grief, or distress that worsens over time are clear reasons to seek support from a professional to aid in recovery.